This article delves into how the body produces power using excerpts from a top surgeon and a research director, who together were at the forefront of sports medicine. I read their article in 1986 (Esquire Magazine) and I’ve kept in my files. Power is at the forefront of golf and this article adds a different perspective.

Many write or speak about how a golfer can gain more speed. Usually it involves biomechanics and the kinematic sequence where they talk about kinetics and the forces that act on club. All of this is good information- all are steps forward in achieving more speed. Let’s look deeper.

In this piece, I insert “golf” whereas it was not part of the original Garrick and Gilhen article.

Details were removed from the original piece. This includes names, different sports examples, and more detail about the intricacies of human performance. There was more description about the nervous system that I condensed.

You can read Part 1 here, or the entire piece here.

The Power Muscles

The Back

The ridge you feel on both sides of spine, running all the way up from the small of your spine, consists of seven muscles known collectively as the sacrospinalis, or erector spinae. Starting at the bottom, the iliocostalis lumborum originates at the top of the big hipbone (ilium) and inserts at the lower six ribs. If you are sagging forward from the waist, this is the muscle that contracts to pull you erect.

From there on up, the rest of the muscles attach to a succession of vertebrae and ribs, allowing for precise control and considerable flexibility in twisting movements of the trunk. On the inside, the quadratus lumborum also starts at the ilium and inserts at the twelfth rib (a “floating” rib, the lowest one in the back) and the upper four lumbar vertebrae. It flexes the vertebral column from side to side. These muscles keep the spine in the middle of the action with every throw, kick or blow.

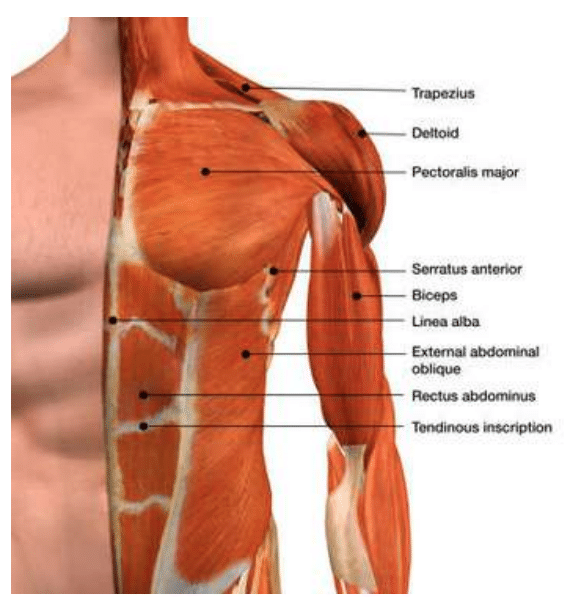

The Abdomen

Here’s where your sit-ups come in. The rectus abdominis, the big, ridged, midline column of muscle that looks so impressive if you’ve worked on it, flexes the vertebral column – that is, it folds you upward. It originates at the pubic bone and runs up to the breastbone, attaching to a couple of ribs along the way. The rectus is an easy one to build up. But the external and the internal obliques, which run from the rib cage to the pelvis, are equally important. Not only do these great sheets of muscle keep your guts in (the anatomy book calls it, politely, compressing the abdomen), but contracting one side or the other bends the vertebral column to that side.

Now here is the hitch. Physical activities involving our legs – most of them, in other words – strengthen the hip flexors but leave the obliques relatively weak. That makes the pelvis and belly tilt forward, arching the small of the back and contributing to the back trouble from with 80 percent of American adults suffer at one time or another. “The abdominal muscles are the guy wires to the back,” says Robert Boston, a trainer of athletes at the New Breed Clinic in Houston. “The stronger they are, the stronger the back.”

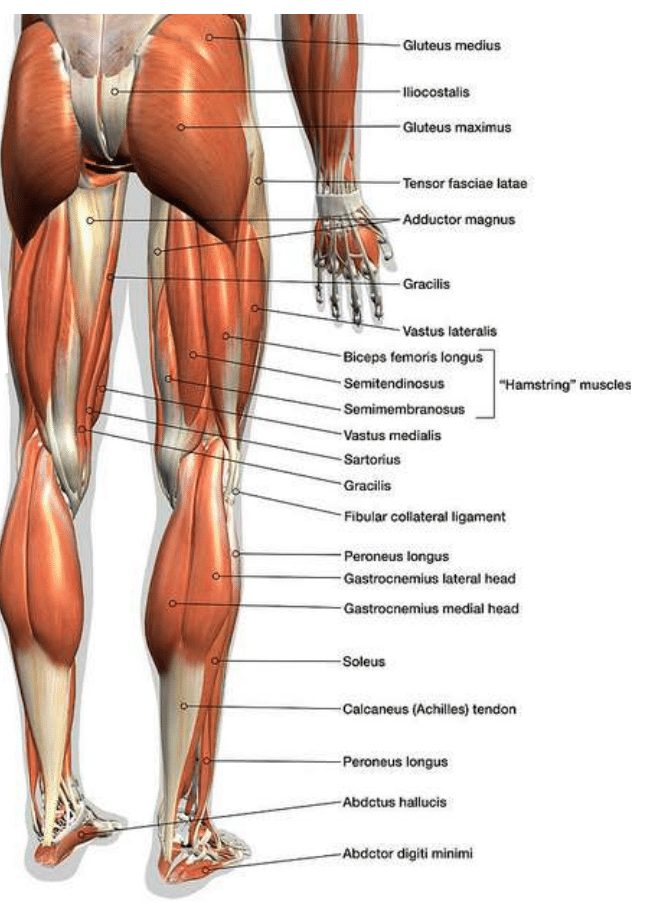

The Thighs and Buttocks

The sheer size of the main propulsion muscles (hamstrings, quadriceps, and gluteus maximus) overshadow other muscles in the same area. Abductors that pull toward the inside of the thigh, and the tensor fasciae latae that pulls to the outside – whose job is to keep you from falling over when you’re propelling yourself- both are overpowered by the propulsion muscles.

The arms are not the only parts of the body with biceps muscles: the biceps femoris is a long muscle in the back of the thigh that you use much more than the biceps brachii in the arm. It is one of the three muscles – the others are the semimembranosus – collectively called the hamstrings. Originating at the pelvis, they cross two joints, the hip and the knee. Together, and in opposition to the quadriceps femoris in the front of the thigh, the hamstrings flex the leg and extend the thigh. Quadriceps means “four heads of origin” as biceps means two. The quads consists of three vastus (large) muscles – vastus lateralis, vastus medialis, vastus intermedius – and the rectus femoris. All four attach to the kneecap with a common tendon; but only the rectus femoris originates at the pelvis.

Ben Hogan wrote about the bicep muscles in his seminal book “Ben Hogan’s Five Lessons: The Modern Fundamentals of Golf (1957),” “At one and the same time, the muscles of the right hip and the muscles of the right hip and the muscles of the right thigh-both the inside and the powerful outside thigh muscles-start to move the right hip forward. In order for them to do this work, these muscles must be stretched taut with tension that is just waiting for the golfer’s signal to be released. This tension is built up on the backswing by retarding the hips but rotating the shoulders fully around. If you permit the hips to turn too much on the backswing, this tension and torsion are lost and then there’s nothing to start them forward. Imagine that, at address one end of an elastic strip is fastened to a wall directly behind your left hip and that the other end is fastened to your left hipbone. As the shoulders turn the hips on the backswing, the elastic is stretched with increased tension, when you start turning the hips to the left, the elastic will snap back to the left with tremendous speed. Same thing with the hips. The greater the tension, the faster you can move them. The faster the hips move, the better. They can’t go too fast.”

You do two-part stretches for the hamstrings and the quads. You can stretch both the upper part the hamstrings and the quads. You can stretch the upper part of the hamstrings just by bending your hips into a semi crouched skiing position. If you want to stretch the top and the bottom, reach down and touch your toes (preferably sitting on the floor, to ease the strain on your lower back). Same idea with the quads. First reach behind you and grasp an ankle with the opposite hand (left ankle in right hand) and pull the heel toward the buttocks. Then extend that leg from the hip. The first move stretches the quads from where they attach at the knee. The second puts an additional stretch on the rectus femoris where it attaches to the outside edge of the big hipbone, the ilium; you’re stretching both ends of the muscle.

I point out in the X Factor writing and in my talks worldwide how the hips and shoulders operate in a power golf swing. The low end of the hip turn is 40 degrees and the high end is 65 degrees. Modern biomechanics has proven these original numbers to be correct. You must not turn the hips and shoulders in tandem. This would require a round house, rotation and a very weak coil. If you stay in your forward tilt, you cannot physically turn more than 65 degrees. In my opinion, the hips can’t turn too fast in the downswing as long as the sequence is correct and there is enough lateral motion to transfer weight/pressure. But I caution that there is more lateral motion in a short iron swing than a driver.

In action, a two-joint muscle is always stretching one end while relaxing the other. When you bring your leg forward to stride, you stretch the top of your hamstrings and relax the bottom. In golf when you dig in with your feet and then push off the ground, you straighten the knee, which stretches the bottom of the hamstrings – and at that instant you extend the hip, relaxing the top of the hamstrings (ground force). The muscle stays about the same length even while it’s doing a lot of work. When things do happen in sequence you get a surge of power with no equal and hit a golf ball further than you could ever imagine. Kinematic sequence in golf is: feet, pelvis, shoulders, arms, hands in that order.

Look at Bubba Watson, Collin Morikawa, Matthew Wolff, Cameron Champ, or Justin Thomas. They propel a golf ball further than almost all golfers, and with phenomenal accuracy. You cannot explain the sinew and bone and muscle alone because none of them look like Mr. Olympia! You ask yourself how they can do it and look so graceful.

The reason is that throwing and striking games are really full body sports, in which you use the upper extremities and the club as you would use the end of a whip. Slow motion video analysis and biomechanics make you truly appreciate how the clubhead lags deep into the downswing. When you see the frames in slow motion the golfer’s trail wrist is cocked to the maximum at what I call the delivery position Step 5 “Build Your Swing”. The arms are accelerating so fast that the shoulders, as Dr. Garrick points out, “are used as decelerators to keep the arms from flying out with the ball after impact”. Top golfers have the sense of “the arms flying off the body” at extension position after impact (Step 7b). This is a common feel that top golf professionals express when describing their swings.

This is why video was a game changer in teaching and so much better than pictures. You see what proceeds, and you see what comes after. Old time teachers used pictures to teach the swing. As a result, many clichés in golf are dead wrong and they remain to this day.

This is the second in a five-part series from Jim McLean’s The Complexity Of Power In Golf, which can be read in full here. In Part 3, McLean delves into Making It Work and Back To Power.